The last Thylacine died in the Hobart zoo in 1936. Or, did it?

The Thylacine species first appears in the fossil record around 30 million years ago.

Their closest living relatives are wolves, and numbats, and a variety of species have been discovered, ranging in size from rodents to large dogs.

Modern Thylacine evolved around 4 million years ago.

They were once common, and fossilised remains have been found right across Australia, and even Papua New Guinea. They are depicted in Aboriginal rock paintings from Western Australia as recently as 3 000 years ago.

Indigenous people hunted the Thylacine, which placed pressure on the mainland population.

This was compounded by the arrival of European settlers in Australia in the 18th century. The Europeans also hunted the animal, encroached on its natural habitat and introduced dogs, who became a natural competitor.

By the mid 1800s, Thylacines were extinct on mainland Australia. Only the isolated population on Tasmania remained.

The Thylacine was a striking looking animal.

Its hindquarters were prominent, raised higher than the front part of its body, and its torso looked entirely too long for the rest of it, like it had been stretched.

Thylacines had a narrow, angular face, and an enormous maw. Their long, skinny snout could open very wide, and was filled with sharp teeth. They were ruthless, and very effective, hunters.

Thylacines were nocturnal, and shy, preferring to remain out of sight. They lived in pairs, one male and female, and had a pouch for their young, like other marsupials.

But their best know feature was their coat. The Thylacine had a striped pattern along it’s back, that caused it to be dubbed ‘The Tasmanian Tiger’.

Europeans began arriving in Tasmania in the late 18th century.

The first settlers were whalers, who camped along the north coast. In 1803, the British government established a town on the Derwent river in the island’s south, to head off a likely territorial claim by the French.

The new town was named Hobart, after the British Colonial Secretary of the time, Lord Hobart. Similar to Sydney, Hobart’s original inhabitants were transported convicts.

Tasmania is a lush place with a cool, temperate climate.

The new inhabitants found it very similar to England, which was a relief after the more extreme environment of mainland Australia. They also found it was perfect for sheep farming.

Land was available on application from the local authorities, to anyone willing to come to this remote outpost and stake a claim. Free labour was also available, in the form of convicts, who could be assigned to landowners and forced to work for them.

It was the perfect business opportunity for the adventurous. From the 1820s onward, a growing number of Europeans arrived in Tasmania, and the local agricultural industry began a sustained boom.

This expansion had a dramatic impact on natural environment.

And one of the effects was a sharp decline in the Thylacine population. Similar to what had happened in mainland Australia, their habitat was taken over for farming, and they were pushed into smaller, and remoter, areas.

Thylacines were also aggressively hunted.

Although rarely sighted, there were rumours that the stripey local Tiger was a poacher of chickens and lambs.

A widely circulated photo (above) shows a Thylacine making off with a chicken, although the photo was later revealed to be fake. It was staged with a dead, stuffed, Thylacine.

Nevertheless, farmers were advised to watch out for the Tigers, and shoot them on sight.

In 1830, the local authorities went even further, and introduced a bounty of 1 pound, per dead Thylaince. Professional hunters and trappers fanned out into the Tasmanian wilderness, and began ruthlessly pursuing these elusive animals.

Thylacines were being pushed to the brink.

By the 1920s, Thylacines had become extremely rare in the wild.

The sharp decline in numbers did not stop people from killing them when they did encounter them. As late as 1930, Wilf Batty shot a Thylacine he spotted on his farm, the last known kill of a wild Tassie Tiger.

But in this era, people were also beginning to wake up to the idea of animal conservation.

In 1928, a Government Advisory board proposed a Thylacine sanctuary, to protect what remained of the species. The proposal was debated by the Government, but advanced only slowly.

In 1933, an adult male Thylacine was captured in dense forest in the Florentine Valley, west of Hobart.

He was given to the Hobart zoo, and later dubbed ‘Benjamin’.

The zoo had Thylacine specimens before, but had not attempted to breed them. As the adults had died, they had simply replaced them with newly acquired animals.

Later that same year, naturalist David Fleay filmed Benjamin on a primitive movie camera. This short film, less than 60 seconds of footage, is the only confirmed video ever taken, of a living Thylacine.

The above clip shows a colourised version, restored by the National Film and Sound Archive.

On July 10, 1936, the Tasmanian Parliament passed legislation declaring the Thylacine an endangered species, and prohibiting their killing.

Benjamin, the last Thylacine, died of natural causes on September 7, 59 days after the conservation legislation took effect.

The Hobart Zoo tried to find a replacement for Benjamin, and sent trackers out to known Thylacine habitats. The search would continue, on and off, for two years, but no animals were sighted.

While there have been numerous claims of Thylacine sightings in the decades since, none of these have been confirmed.

In 2021, The Thylacine Awareness Group of Australia made world headlines, with a video they claimed showed a living specimen in the wild.

The privately funded group places remotely triggered camera traps in remote locations, to try and capture Thylacine footage. A screengrab from the video is shown above (you can watch the full video with a 20 minute discussion, here).

Wildlife experts were sceptical, claiming the animal was far ore likely to be a fox or a pademelon.

The search, and debate, are likely to continue. Tasmania's rugged terrain, and the Thylacine's preference for remote habitats, will make it difficult for some people to accept that their couldn't be living specimens.

And other species, considered extinct, have been rediscovered. There have been enough examples for this to even have a name: they are called a 'Lazarus Taxon'.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) requires a period of 50 years without the sighting of an animal, before they will declare it extinct.

For the Thylacine, this was reached in 1986. From this time the Thylacine officially joined the sad ranks of the Dodo, the Passenger Pigeon, and the Baiji Dolphin.

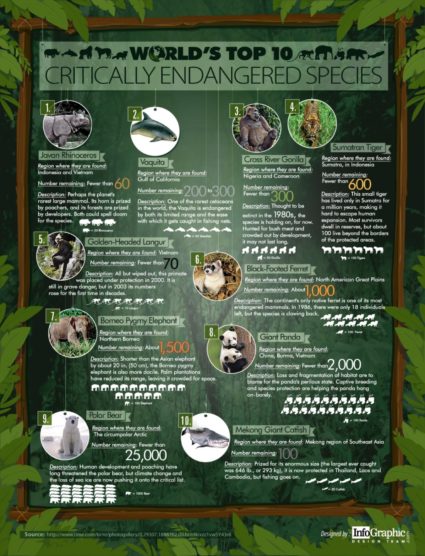

As of 2014, IUCN lists more than 2 400 animal species as ‘Critically Endangered’, teetering on the verge of extinction.