Quirky statues, lush forest, a labyrinth of stone pathways; The William Ricketts Sanctuary is an artistic legacy unlike any other.

William Ricketts was not obviously destined for an artistic life.

Born in 1898 in industrial Richmond, in inner Melbourne, his early years were grounded in gritty reality. His father was an ironmonger, and he was the youngest of five siblings, in a household where money was tight.

Ricketts attended secondary school in Thornbury but was a lacklustre student, and frequently played truant.

After graduating he was directionless for a few years, working a variety of menial jobs. Significantly, one of these was for the Australian Porcelain Company, where he helped manufacture homewares and learned the principles of basic design.

Ricketts subsequently began to take an interest in the arts.

In his twenties he met Gustav Pillig, a German artist who had emigrated to Australia. Pillig was best known for his sculptures; striking, stylised depictions of men and women, usually nude, dramatically posed.

Pillig was also a dedicated naturalist, and produced a series of landscape paintings, showcasing the regions around Melbourne.

It was Pillig who introduced Ricketts to the writings of Baldwin Spencer.

Baldwin Spencer was a British anthropologist, who had become obsessed with Australia’s Indigenous culture.

Spencer had first come to Melbourne in 1887, where he was employed as a Professor of Biology by Melbourne University. In 1894, wanting to see more of the country, he joined a scientific expedition that was to explore the outback.

Departing from Adelaide, the party headed north and roamed the desert around Alice Springs, covering 2 000 km in three months. They encountered several Indigenous tribes, and documented the native flora and fauna. It was a fateful trip for Spencer, who was struck by both the people and the country.

He would return to the outback repeatedly in the ensuing three decades, and produce some of the first serious western writing about traditional Indigenous culture.

Pillig gifted Ricketts a book written by Baldwin, called ‘Arunta: A Study of Stone Age People’. Ricketts read it voraciously, and quickly became obsessed with Indigenous culture himself.

He had also decided to focus on becoming an artist.

In the early 1930s, Ricketts began to sculpt, creating ceramic works that reflected his interests and influences. Many of these took an Indigenous theme, or depicted Indigenous people, others were concerned with the natural world, and the damage done to it by modern society.

His works received a mixed response. They were judged to be passionate, and imaginative, but also lacking in skill and subtlety.

But Ricketts was able to generate enough income from his sculpting to purchase a large property on the outskirts of Melbourne. This tract of native forest, on Mount Dandenong, near Olinda, was intended as an artist’s retreat, and hideaway.

Ricketts moved there to live in 1935, and was joined by his mother two years later.

They lived in a primitive wooden shack and tried to subsist as self-sufficiently as possible, growing their own food and using water from a diverted stream. Ricketts augmented this basic lifestyle with income from his art.

He exhibited a dozen more times in the next ten years. And while the critical response to his works never advanced beyond modest, he was still able to develop a following.

His interest in Indigenous culture, and use of their iconography in his work, brought him to the attention of Melbourne’s Aboriginal community.

Several local Indigenous leaders, including well-regarded figures like Douglas Nicholls, were among Ricketts supporters, and helped introduce and promote his shows.

Ricketts spent most of his time in his mountain retreat, sculpting, and carving rambling pathways through the native forest. He decorated these with his own art, creating a natural, outdoor gallery.

By 1949, Ricketts was secure enough financially that he could finally indulge a lifelong passion; he began to travel to the outback, to experience first hand the Indigenous culture he had read about.

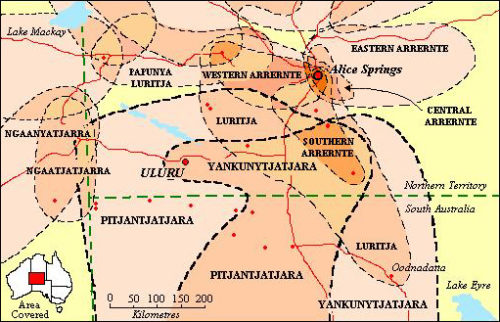

He spent several months with the Arrente and Pitjantjatjara tribes in Central Australia, living a simple life in the desert.

He brought sculptures with him to present to local artists, and tried to incorporate Indigenous ideas and artistic traditions into new pieces. He also contributed to a gallery at Pitchi Richi, outside of Alice Springs, which now houses a significant collection of his work.

Ricketts described the sculptures he produced in the outback as ‘totemistic’. He would continue to visit the area regularly, through the 1950s and 60s.

In 1961, Ricketts agreed to sell his Mt Dandenong property to the Victorian Government.

The deal would preserve the ‘Sanctuary’ as a public park after his death, while the government also agreed to build Ricketts a modern house, studio and kiln.

He would live there for the rest of his life. While officially known as the William Ricketts Sanctuary, the artist himself had a different name for the property; ‘The Forest of Love’:

‘I use clay. It opened up my love for the country, the earth, the clay, the wild life. I am part of that … I am trying to share what the Aboriginal gave me.

It is not the William Ricketts Sanctuary, it is the forest of love.’

- William Ricketts

The William Ricketts Sanctuary is a popular spot for weekend visitors up Olinda way.

I visited this week and it is a lot of fun; quirky, passionate, and popular with kids, who ducked among the exotic statues, playing some kind of secret agent game as they ran up and down the winding stone paths.

A fitting legacy, for an individual who followed his own unique path.

I’m very sad it has been sitting since June 2021 storm event and not yet reopened. I loved taking visiting friends and family here, it was always worth the drive from the city. I am hoping they put a plan in place and they open it again. They have spent so much money on the local gardens but I am yet to see any announcement on this sanctuary.

I met William Ricketts in 86/7. I used to go up to the sanctuary as I found it peaceful and calming and I had recently gone through a bad time having been falsely accused of computer crimes of producing illegal discs for sale which eventually turned out to be mistaken identity. I was probably the only person there one Sunday and wandered into his studio area and was looking at photos of old Australia when he walked in. I said I was interested in what happened and he took some large photos out of a drawer under a big table which showed huge traction engines with balls and chains between being dragged to clear the bush. I only found out a year after who he was when I saw a photo in Melbourne Arts Centre.

My wife and I visited The Forest of Love in the late 1990’s, and were very much taken with its spiritualism. We had heard of it in the UK through the Billy Connolly documentary series of his travels around Australia, and were quite surprised when we visited family in the Melbourne area, that they had no idea what we were talking about. We were determined to see it, and so hired a car to make the journey for that sole purpose. I have a couple of books on the subject, and an old VHS tape of ‘The Forest of Love’. For some time now, I have been trying to find out how to get a copy on DVD, but without success. If there is anyone that can help in this regard, it would be greatly appreciated.